MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE BOOK

In this blues guitar PDF, you'll learn how to get started with playing the blues when it's just you and your guitar. Over the years, learning the blues has largely become a multiple-person affair — at the very least, someone usually needs to play the rhythm while someone else plays the solos.

But the thing is, the players of old mostly handled every facet of a blues tune by themselves. They sang it, played the rhythm, took all the solos and didn't have to rely on anyone else to be around for a song to sound complete.

Most of the time, you probably play guitar all by yourself, and if you go about it right, you don't need anyone else, either.

Here's a sustainable approach that you can use to play the blues when it's just you and your guitar.

The Chords

Any type of solo guitar playing requires you to weave individual lines of music around chords. Most commonly, the blues requires you to know three chords, contingent on which key you're playing in. In the key of A, the three chords are A, D and E. You can use any variation of these chords, including the basic open ones you learned when you first picked up a guitar.

But when you're playing solo style, you also want to make use of chord shapes that allow your hand to move efficiently between the rhythm and lead playing, so that you can more intuitively do complex things.

The Rhythm

One of the characteristics that makes blues so distinct is its rhythmic quality — it swings, ya dig? The swing rhythm comes from a

4/4 strum based around triplets, which is a music term meaning that instead of a beat divided into two, it's divided into three.

Somewhat confusingly, triplet notes are considered eighth notes, and while you would usually count a four count that contains straight eighth notes as 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and, you count one with triplets as 1 triplet 2 triplet 3 triplet 4 triplet.

The most common triplet-based, four-count strum pattern for blues is called "swing eighths." The swing eighths pattern is played by hitting a downstroke on each number, playing nothing over the "trip-" syllables and then finishing off the sequence with an upstroke on the "-let" syllables. You also need to heavily accent the 2 and 4 beats of the count.

The 12 Bar Blues Progression

The most important part of the blues is nailing down the basic chord progression. Most people are unaware, but there are actually multiple progressions that can be used for the blues. Far and away, though, the most common one is called the 12 bar blues, so named because to get through the whole thing, you have to play 12 full four counts, called bars or measures, terms that are used interchangeably.

It can't be overstated that to be an effective blues player, you absolutely have to know the 12 bar blues like the back of your hand. Realistically, glossing over the chord progression is the number one reason people fail to gain traction with the blues.

To be any blues player worth your salt, it's not enough to simply know it. You have to know it to the point that you never make the mistake of getting lost in it. The reality is that everything blues players do is centered around a chord progression, and you can know all the fancy licks in the world, but if you stumble through the chords, it makes you look like a rookie.

One final thing to note about the 12 bar blues is that in it's purest state, the final bar is actually another A chord, but most of the time that measure is used to help send the progression back to the beginning and is called a turnaround measure. While there are many ways to play a turnaround, in this case, going to the E is the simplest and safest choice.

The Am Pentatonic Scale

The quickest and most effective way to approach improvising blues licks is to learn the pentatonic scale, and then learn how to move it around and manipulate it for what you're doing. There are two versions of the pentatonic scale, the major and the minor. To play either version on the guitar, the patterns are the same, they're just played in different places. In total, there are five different patterns, called positions, and they all connect to each other. At this point, however, you'll only need to learn one, the first position the minor pentatonic in the key of Am.

How to Make Your Own Guitar Licks

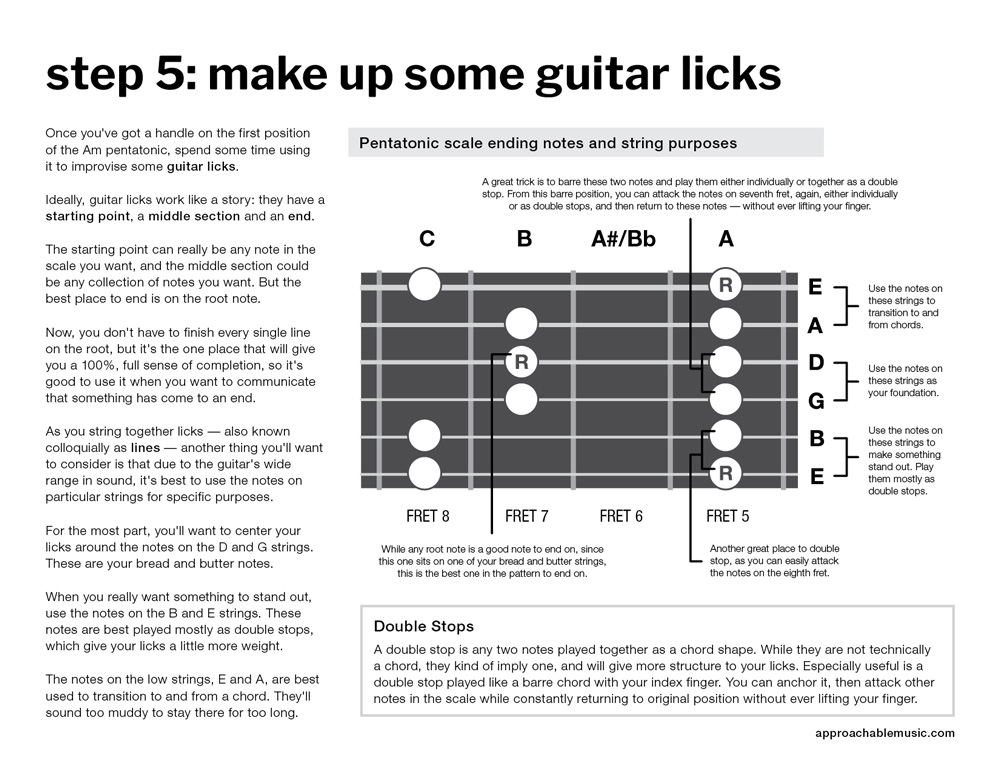

Once you've got a handle on the first position of the Am pentatonic, spend some time using it to improvise some guitar licks.

Ideally, guitar licks work like a story: they have a starting point, a middle section and an end.

The starting point can really be any note in the scale you want, and the middle section could be any collection of notes you want. But the best place to end is on the root note.

Now, you don't have to finish every single line on the root, but it's the one place that will give you a 100%, full sense of completion, so it's good to use it when you want to communicate that something has come to an end.

As you string together licks — also known colloquially as lines — another thing you'll want to consider is that due to the guitar's wide range in sound, it's best to use the notes on particular strings for specific purposes.

For the most part, you'll want to center your licks around the notes on the D and G strings. These are your bread and butter notes.

When you really want something to stand out, use the notes on the B and E strings. These notes are best played mostly as double stops, which give your licks a little more weight.

The notes on the low strings, E and A, are best used to transition to and from a chord. They'll sound too muddy to stay there for too long.

The A Major Pentatonic Scale

While the Am pentatonic scale can help jumpstart your blues playing, it's kind of overkill when it comes to blue notes. In general, blue notes have more impact when they contrast some of the more vanilla notes in the key. So, a better scale to use as a foundation for improvisation in the key of A is really A major pentatonic, which can be found by moving the Am pentatonic pattern three frets back. Now, your index finger starts the pattern on fret 2.

Taking the Major Pentatonic Scale Up a Notch

Mostly, you can approach improvising in the major pentatonic as you would the minor — you'll still want to make good use of double stops and also want to use each string set for their appropriate purposes.

But there are a couple things you can do in the major that can take your playing up a notch. First, you might notice that a basic open A chord covers a few scale notes on fret two.

By playing this chord instead as a three-note barre chord with your index finger, you can play it like a chord on beat 1, and also use it like an anchored double stop for the guitar lick. From there, you can attack other notes in the scale while never leaving the chord position, which makes switching between rhythm and lead as intuitive as it gets.

There are also two important blue notes that can be mixed in to your licks that can give you a bluesy sound without going overboard.

The flat seven note (b7), can be found on the fifth fret of the D string and the flat third (b3), which is considered the ultimate blue note, can be found in two places: on the A string of the third fret and G string of the fifth fret.

Any of these notes can be used in addition to the other notes in the major pentatonic. While there are other places within the pattern to find these blue notes, these instances are the easiest to use from the anchored A chord.

A Basic Approach for Mixing the Major and Minor Pentatonic Scales

In every type of music, your default scale for creating guitar licks should be the major pentatonic scale, and realistically, save for special circumstances, you should avoid using the minor pentatonic all together.

The blues, of course, would be considered a special circumstance. Because of the music theory behind it, the minor pentatonic has a lot of blue notes that fit well into the style.

But rather than overdo it by using the minor pentatonic exclusively, it's better to take advantage of it by having a solid approach.

At this point, it should be noted that like anything else in music, the blues can be transposed across all keys. With that in mind, here are some rules of thumb to start with. Over the A chord (or any other 1 chord), play the major pentatonic. Over the D chord (or any other 4 chord), play the minor pentatonic. Over the E chord (or any other 5 chord), play the minor pentatonic.

This approach works well because even though you play the minor over more chords, you actually play the major over more measures. This will help spread out your use of blue notes without you having to think about it too much.

Beyond the Blues

The techniques in this guide are only a starting point. Ultimately, there are only two main rules solo guitarists must always follow. They can never get lost in the chord progression and never lose the rhythm. Besides that, there's complete freedom to do whatever you want within the boundaries of the progression. But it's a constant balancing act to play licks without making them so long as to drop the rhythmic structure.

In many ways, the two rules are related, and you'll avoid a lot of problems by playing a chord (or something that implies a chord) on beat 1 of a measure and then filling out any spaces with muted up- or downstrokes. But, feel free to explore the limits, as well.

Personally, I often play licks that cover two measures, getting away with it by using double stops and bass notes to imply chords. The best advice is to start from a standpoint of strumming and gradually increase the amount and length of licks throughout the progression. That means, if you want a lick to run through the 4 beat — do it. But, always, once you lose the rhythm, you've taken it too far.

At the end of the day, the blues is simply built on a chord progression, the major pentatonic scale and a few added notes for embellishment.

The technique of mixing chords and licks, however, is not exclusive to the blues and can realistically work over any chord progression in any style. You'll just have to remember to remove the minor pentatonic scale and probably, depending on how they sound, any other blue notes from the equation.

The easiest way to start exploring how this works beyond the blues is to find a song with a simple progression and start combining chords and licks perfectly throughout.

Use the basic open chords and improvise with the major pentatonic only. As a basic guide for soloing, follow the rhythm of the song's melody. You don't have to play the melody note for note, just follow its phrasing rhythmically. When it's time to sing, simply strum the progression.

You'll really be able to run with this concept by learning all five positions of the major pentatonic scale, as well as how to move it. Some positions simply work more intuitively with certain chords, which will make your left-hand movements more efficient, so you

can do complex things more quickly.

Plus, it's a minimal amount of work to really gain a strong foundation for advanced playing. Know the five positions well, and difficult music concepts become much easier to learn.